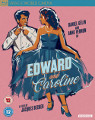

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Edward And Caroline (1951) Film Review

French director Jacques Becker became known throughout his career for his attention to detail - the little things that people do, which make his films feel more naturalistic than many of his contemporaries, while nodding towards the Nouvelle Vague to come. This skill is in evidence from the very outset of Edward And Caroline, when the camera drifts from a view of the street to pianist Edward practising arpeggios and we see Caroline, through the door of the neighbouring room, washing out the bath. It's the sort of incidental moment that is rarely captured in a fiction film and certainly not something that you expect one to open with. But the fact it is an act of such little importance is exactly what drives the intimacy of it. We immediately see in this environment something we can relate to and we also learn about the intimacy of the couple - he able to play while she, presumably, bathes with the door open.

We soon learn that their relationship is not without friction, she offering him a kiss and a boot as he leaves the apartment in search of a corsage. We'll be following them over the course of one night during which Edward (Daniel Gélin) will endeavour to impress the friends of Caroline's (Anne Vernon) much wealthier uncle. Becker is less interested in plot machinations than the vagaries of character, developing his film into something that is part screwball romp and part social satire, part chamber piece.

Some of the spark between the couple stems from their difference in class but Becker doesn't draw simplistic conclusions, also showing that they are both strong-willed people with taste that doesn't always overlap. The action plays out against the backdrop of their decidedly bijou and cluttered apartment and the contrasting grandeur of the mansion owned by her Uncle Claude (Jean Galland) as, through the night, the couple's arguments will see them embark on a borderline farce between the two buildings.

The plot is as floaty as Caroline's evening gown but the joy is in the minutiae - we feel the anger of Caroline at one point, not because of the lines she is given but because she starts trying to bite Edward, and Becker elegantly illustrates their divergent taste in the way they turn on and off the radio. The radio also illustrates Becker's ability to generate atmosphere via diegetic sound, a technique he would go on to use to even greater effect with the head gangster's favourite record in Touchez Pas Au Grisbi. The use of the piano is also cleverly worked. We're all familiar with films in which the actor is clearly not playing the piano - the camera tastefully pulling away so that we can't see the keys, but here a genuine pianist snaked his hands round Gélin so that it genuinely looks as though he is playing.

Beyond these sorts of impeccable technical details, the lively script has, on the whole, aged well. The sight of the beautiful Elina Labourdette as Claude's posh guest Florence Borch de Martelie, attempting to seduce her host with a look is as funny today as it ever was, as is the satirical swipe at the upper classes when, after they have looked positively stultified as Edward plays a classical piece, suddenly spring into life in order to perform the dance steps to a throwaway tune of the day. There's also some fun with the foreign guests, including American Spencer Borch (William Tubbs), who turns out to know more than his hosts about culture.

A late in the film "rape" joke has, however, not stood the test of time and it's unfortunate that in the latter stages the enviable balance that Becker and his co-writer Annette Wademant had achieved - no doubt because some of it was based on their own somewhat volatile relationship - begins to lurch in favour of one party over the other. It's unlikely that the audiences viewing it on release would have seen this as a shift to darker territory but watching it today, it's hard not feel a bit disappointed after all that has gone before.

Reviewed on: 24 Aug 2017